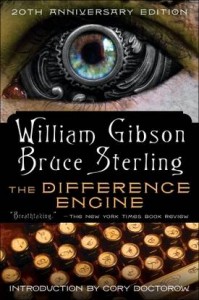

Vår hedersgäst Cory Doctorow har skrivit en introduktion till The Difference Engine (1990) av Bruce Sterling och William Gibson, och dessutom var han så snäll och sade att vi får publicera den på denna vår hemsida. Tack, Cory!

The Difference Engine: A Generation Later

The greatest irony of The Difference Engine is that it’s easily the most prescient novel from either Bruce Sterling or William Gibson, both authors with a reputation for successful futuristic prediction. Of course, both writers disavow any capacity for prognostication — Gibson happily and famously admits to practicing ”presentism,” not futurism; that is, using the literary device of the future to tell stories about the present.

The greatest irony of The Difference Engine is that it’s easily the most prescient novel from either Bruce Sterling or William Gibson, both authors with a reputation for successful futuristic prediction. Of course, both writers disavow any capacity for prognostication — Gibson happily and famously admits to practicing ”presentism,” not futurism; that is, using the literary device of the future to tell stories about the present.

It’s true that Gibson and Sterling have inspired plenty of futuristic effort; Sterling’s environmental/design manifestos influenced a generation of tinkerers and designers; Gibson’s matrix fired the imaginations of plenty of 3D virtual world creators, Web developers and other network-makers. But inspiration isn’t the same as prediction: when Nokia engineers paid homage to the Star Trek communicator with their flip-phone designs, it wasn’t because Gene Roddenberry foresaw a true vision for the future of mobile communications. It was because telcoms geeks watched Star Trek.

Today, there is a thriving steampunk subculture — costumed and bewigged, energetically publishing zines (even print ones) and all manner of clockwork-encrusted ephemera and tchotchkes. They gather in large numbers for conferences. They argue about what is and isn’t ”real steampunk.” There are steampunk club nights that host steampunk bands. There are steampunk sex toys. (Is there steampunk porn? Actually, not as of this writing; I’m guessing it’ll be landing on a search engine near you any day now).

The most interesting thing about modern steampunk (you should forgive the expression) vis-a-vis Sterling-Gibson prescience is that practically none of it was inspired by The Difference Engine. The average steampunk at the events I attend seems to be in her or his mid-twenties, about the same age as this book. The Difference Engine was not a timebomb, waiting to be discovered by an identity-hungry generation 20-some years after it first saw print.

No, the Difference Engine did not inspire steampunk, but it surely did predict it.

The thing is, being a steampunk is weird. It’s even weirder than being a science fiction fan (not merely someone who reads science fiction, but someone who identifies with the science fiction subculture — someone who’d live in the science fiction quarter if his city had such a thing). It’s weird enough that finding other potential steampunks — or even discovering that steampunk exists and having that frisson of these are my people — is a serious challenge.

Or at least, it was a serious challenge, 25 years ago, before Google made all that subcultural stuff as easy as a search-term. There’s the real prescience in Gibson and Sterling’s work of the day: at the time when AT&T was boldly predicting that the Internet would come along and make us all more normal (”Have you ever tucked in your daughter from

3,000 miles away? You will.”), these guys were promising that it would make us weirder than ever. It would make it possible for the happy mutants lurking among us to discover one another across the miles and the years, and to industriously trade elaborate leather-and-brass garments, improbable prop rayguns, and entire Burning Man-loads of goggles.

Why has steampunk caught fire now, in the midst of the networked society, ten years into the relentless WTO era of global trade? I think the answer is in the motto of the excellent Steampunk magazine: ”LOVE THE MACHINE, HATE THE FACTORY.”

The factory might have given us the millionfold productivity increases that yielded the industrial revolution, but it achieved those gains by chaining us to machines, deskilling the artisan and turning him into a cog in the factory, stripped of judgment and dignity and disconnected from the rhythms of his spirit and the world around him. An artisan carpenter might have gone outside to sand lumber on a fine spring day when the air was blossom-scented and stayed inside to varnish on a freezing day when the stove’s heat defied the elements. But a factory worker can’t choose her tasks or their timing: that is dictated by all the intricate interdependencies with which she is enmeshed. The factory might produce the same door at 1/1000th the price, but at a brutal and incalculably high human cost.

At its root, steampunk venerates the artisan, celebrates an abundance of technology, and still damns the factory that destroyed the former’s livelihood to create the latter. Contemporary steampunk subculture inhabits a contrafactual world in which these contradictions are resolved — where ”the street finds its own use for things” and where makers can produce wonderments that simultaneously embody lightspeed technological change and enduring artisanship (if there was even a gewgaw that illustrated this perfectly, it is the brass-worked steampunk USB thumb-drive, doomed to be obsolete in a year, but hand-wrought to survive for the ages).

The funny thing is, we might just get there. The combination of 3D printers (and other rapid, local fabrication devices) and a networked stuffed with HOWTOs explaining how to accomplish 90 percent of any project (you come up with the remaining 10 percent and publish your results, of course) puts an artisanal, bespoke high-tech practice in reach of everyone who loves the machine and hates the factory and wishes you could have one without the other.

After all, this is the age of collaboration, an era in which it is simpler to work together than ever before. Consider that Bill and Bruce wrote this book by FedExing floppy disks to each other, from Vancouver to Austin and back again, augmented by long, thoughtful faxes debating what should happen next, and compare this to the process by which writers today collaborate. Charlie Stross are writing a novel together by loading text into version control systems that instantaneously collate and track all changes either of us makes.

So here we are, a quarter century after that heroic age when FedExed floppies twined together the words two of the great thinkers of our time, producing this fabulous brick of prose you hold today. A book that prefigured not only a subculture, but a prose-style, the Google-style-of-literature that involves a fiendish density of quirky historical references and oddly vivid details from the most obscure corners of yesteryear and literature — but, incredibly, this wealth of fascinating bits and bobs and pastebombs was harvested by hand from the UT Austin library without so much as a search-engine. Do keep that in mind as you go, visiting this text for the first time perhaps, or revisiting it now after 25 years — today, a hack like me might google up a scattering of fanciful Victorian argot for verisimilitude, but these fine gentlemen got their stuff the hard way, the artisanal way, the steampunk way.

Bravo, sirs.